Two years ago I wrote a couple of blog posts on how to resolve a perceived conflict of interest in insurance (see here for Part I and here for Part II). Back then Laka was called Insure A Thing (read more about our rebranding exercise here) and was little more than a concept with some pretty powerpoint slides and zero lines of code written.

Today, Laka is live in the market and has been trading for about 12 months with an upside-down “community-based” insurance model. We have solved regulatory, legal, operational and product-related issues along the way.

With the learnings of the past two years, do I still believe there is a mismatch between the interests of conventional insurers and their customers?

Yes, more than ever. The business model of conventional insurance is flawed, at the very least for short-tail business. Let me tell you why.

From the insurer’s perspective, it’s arguably the best business model in the world: collecting money from customers first, using it to generate investment income, and only later, after a rigorous process, providing an actual service in paying out a claim.

It would be difficult to design a business model more one-sided than insurance. Did I even mention the excess that keeps the annoying small claims away?

Insurers openly advertise their high payout ratios in areas where they look good, motor insurance for example, known as one of the least profitable lines of personal insurance. With no surprise, it is much less attractive to communicate similar figures for products where there is money to be made and the payout ratios are significantly lower.

For products like travel, personal accident, and, indeed, bicycles, traditionally less than 30p in each £1 in premium is paid out in claims. The remaining 70p evaporates in expenses, distribution costs and profit.

Sadly, the majority of this 70p is often used to generously pay distribution partners commissions to sell insurance products, which requires substantial monetary incentivisation for e.g. travel sites. No doubt the supplemental income is most welcome to these e-commerce platforms.

Insurance is an intangible service that has a mixed reputation in the eyes of consumers because of perceived unfairness (“I have to give you my money first for a possible service from you later”). The natural reaction would be to fix the underlying mechanics to provide a better product / service - in theory at least.

Instead, insurance executives put further fuel to the fire by punishing customers’ loyalty with higher premiums in order to offer cheaper rates to attract new customers. There is an outcry from the industry itself that insurance gets commoditized, and yet insurance companies leave no stone unturned to improve their rankings on price comparison websites to skim volume. More often than not this is achieved by reducing product features to drop the price.

One big insurer recently made the news by publicly avowing to do away with the “loyalty penalty”, and selling this move as revolutionary! You couldn’t make this stuff up.

Over the past two years, I have met many fascinating people working for large insurance carriers with tons of ideas on how to improve the customer experience. And yet, with executives often incentivised by Total Shareholder Return, i.e. short-term measures to please shareholders, change is hard to come by.

More than ever I believe that a complete redesign of the conventional insurance model is required to win back customers’ hearts and to reestablish insurance as the social good it really is.

However, this designed misalignment of interests has gone unchallenged despite advances in technology that allow the reassembly of the value chain for a better customer experience.

Centuries ago, it would have been impractical to collect premiums in arrears. It would have been rather costly to ride from town to town on a horse and collect small payments every month, and impossible to prevent customers from disappearing into the woods (literally) to avoid paying up.

With the technological advances of credit cards, credit scorecards, and payment infrastructure, inter alia, we now have the opportunity to build insurance again from scratch. The opportunity to create a model where the customer truly comes first: receiving a service before the provider gets paid at the end of the month.

Turning the value chain upside down - from underwriting to credit risk

The designed misalignment of interests in insurance can be fixed and Laka has set out to achieve nothing less.

We charge our customers at the end of the month based on the actual cost of claims incurred. Each individual’s monthly charge is capped at a personal maximum based on the value of their insured gear. This takes the form of a stop-loss arrangement provided by a re/insurer.

We have specially earmarked working capital (“claims float”) in order to pay out claims swiftly. This allows us to pay out claims first and only later, post-claim events, we ask our customers for a share to reimburse us. For our services we add a success fee on top of the paid claims. No claims in a month, no pay.

Thanks to the personal cap, set around the price of conventional insurance, the worst possible outcome for customers is that they have to pay what they would have to pay elsewhere. In turn, however, if customers collectively take better care and fewer claims happen, the savings are theirs to keep.

Introducing a new business model does not come without risk. Whilst it is still early days for Laka, let’s take a look at some of the key theories we have to prove en route to making this a commercially-viable business.

Payment default risk in the insurance industry

Our hypothesis is that payment default risk in insurance can be managed. We knew that it had been done in the credit card and lending verticals - why not insurance?

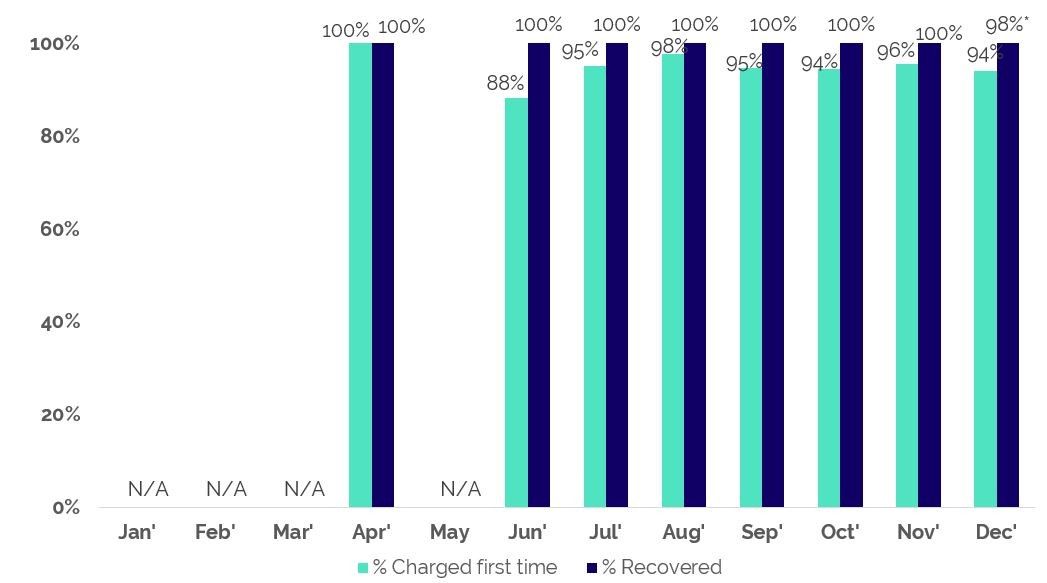

In 2018, we had a gross payment default rate (payments that bounced at first attempt due to expired cards, banks rejecting the charge etc.) of 5%.

Within days of every month end we recovered bounced payments for a 0% net default rate.Yes, until November, not one single customer has failed to pick up their tab (*December recovery cycle still running).

Along the way, we have learned tons in the process of making the billing process efficient and effective, and have begun building our own proprietary credit risk scorecard with some less conventional data points.

Other findings were less obvious at first but now make complete sense. For instance, customers may sign up to Laka with their Strava or Facebook profile - two-thirds are doing so. Initially regarded as means for faster onboarding and possibly fraud mitigation, it turned out that gross default rates for these customers are significantly lower than those we only have an e-mail address for.

No doubt payment defaults will occur over time and we will review these carefully. We continue to be bullish on managing credit risk in the insurance industry.

Flexible payments

One of the most interesting experiments for us was to see if customers would accept flexible payments in line with claims volume. So far the experience is overwhelmingly positive. Despite - or possibly because of - our monthly-renewing policies which don’t tie our customers down, our churn rate is below 1%.

Cancellations have come in two forms. Either customers viewed us as a semi on-demand solution that they use only for the summer months or they didn’t like the variation in the monthly billing. Some people would rather pay a set £10 upfront than a variable £4 - 8 at the end of the month, and we respect that.

The core value that underpins our offering is transparency and our monthly bill tells a story: the more we have to charge, the more cyclists have suffered from thefts and damages.

As one customer put it: “[...] when I have to pay a premium I really don't mind, because I am getting an unfortunate like-minded cyclist back on the road, and I know if that was me, how grateful I would be.”

In turn, if there are fewer claims in a month, we ask our customers to contribute less.

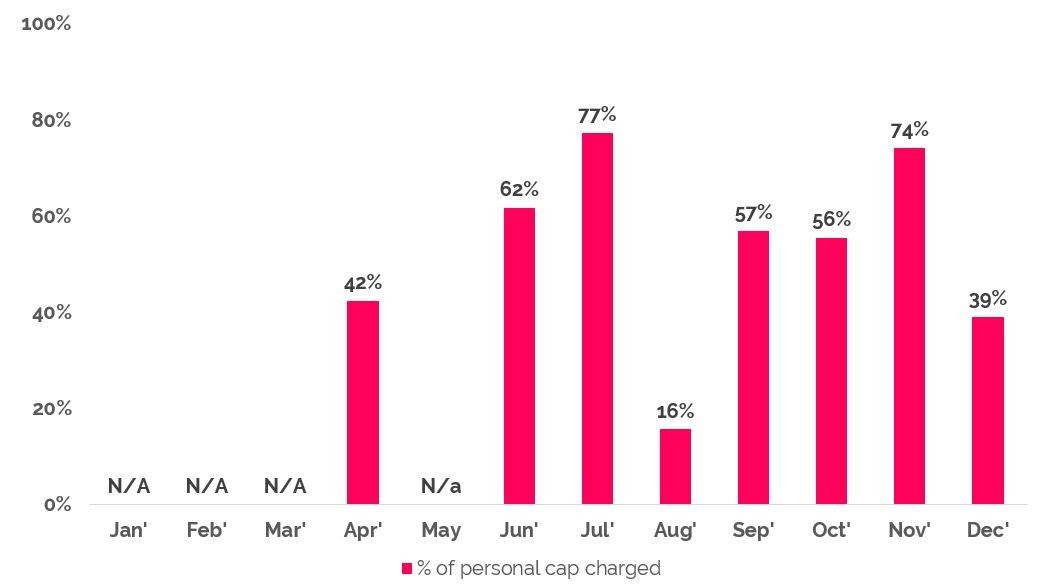

As a disclaimer, we started with literally zero customers when we launched and it took us a while to grow the pool to a meaningful size.

The most important thing to point out is that we haven’t hit the personal cap once. The months of July and November were those when our customers incurred the most claims. In other months we had very few claims (or even none sometimes).

We were surprised to see relatively low claims in August, but that is the beauty of our model - customers only pay what they collectively consume as risk pool.

On average, we charged 35% of the personal cap in 2018. Even if we exclude the first quarter we get to a respectable 47% of the personal maximum. In other words, customers have saved 65% or 53% respectively compared to conventional insurance.

This equates to c£141 in savings over the past 12 months for a customer with a £2,200 bike, the average bike value insured with us. Since our customers insure more than one bike with us, the savings are quite a bit higher. This could buy a really nice Rapha cycling jersey. The EF Education First Pro Team Aero Jersey even comes in Laka colours - ok, almost 😉

Customers’ exposure is capped at around market rate. The worst possible outcome with Laka is to pay what you would elsewhere. What’s not to like?

Two of the key tenets of our value proposition have tested successfully over the last year, with many screws adjusted along the way. We now feel comfortable enough to expand our product offering beyond cycling.

Furthermore, 2019 will see us experimenting with sub-segmentation of our risk pools based on patterns we identified to allow for even closer alignment among Laka’s customers.

A look in the (regulatory) crystal ball

As a business, Laka combines consumer finance and insurance elements. In the UK, however, a consumer finance company cannot take out a stop-loss arrangement from a re/insurer.

When we launched we had therefore decided to go the way of least (regulatory) friction and launch as a Managing General Agent (insurance intermediary). This requires us to have an insurer to underwrite each policy and to provide the working capital in the form of a claims float.

The claims float is subject to Solvency II regulation and is accounted for accordingly on the re/insurer’s balance sheet, making it more costly for us - and in turn our customers.

In a world where we don’t need to provision for uncertain events (we know the level of claims we have to recover from our customers before we bill them), and only need to hold sufficient working capital to be able to pay out claims first, why do we still need to play by rules written at a different time with a different purpose?

Why can’t a consumer finance company take out a stop-loss contract from a re/insurer? Why can’t we obtain working capital from non-insurers, e.g. in the form of a revolving credit facility, or better - in the form of a loan from retail investors?

If retail investors each provide £100 for a fee that is below the cost of our claims float, we would save money and retail investors would gain access to an alternative asset class, in line with P2P lending principles.

What is more, if retail investors provide the working capital to allow Laka’s customers to insure their assets, we would create the first true peer-to-peer insurer where Laka takes the role of a facilitator.

Would less fraud occur if it is known that it hurts other people rather than a large corporate? Would behaviour change if the lender knows who is in the pool of insureds, possibly through the use of social media?

We cannot know the answer until we try it, and I sincerely hope that we get a chance to test it out. We have few ideas at Laka on how to make this happen.

The InsurTech ball has only just started rolling and I’m sure we will see many fascinating attempts to turn insurance as we know it on its head.

The winner in all of this will be the customers who will benefit from more choice at lower cost with a better experience.

Oh, before I forget, we have also launched Laka Club and Laka Trade, offering perks to the cycling community including free of charge third-party liability cover - but that’s a whole different story.

The End.